I’m writing this from my new shop. That’s “my” in various ways. It’s my shop in the same way you may be sitting in your workspace as you read this. It’s also my shop in the sense that I started my own practice after many years at Boor Bridges. But the most important way it’s mine is, to borrow the title of a great, early Michael Pollan book, because it’s a place of my own. Because like Pollan in his book, I as an architect took the lead in constructing this place, my place.

As with many other endeavors that are mine rather than for someone else, this space will never be done. Or at least it will never get as close to done as a project undertaken for a client. Work on this shop will happen when time and resources are available. It will happen in between other responsibilities, not strictly to plan, and largely with my own hands. For now, I am sitting here contemplating my to-do list and listening to someone practice trumpet, the sound making its way through the walls of another building down the alley. It sometimes occurs to me to go find out where it is coming from, but then I don’t. I think I just like letting that sound be a mysterious part of this space, my space.

Dear Inga takes its name from a notion of correspondence, the idea of a letter being written to the past. My work on this recently opened San Francisco restaurant was, similarly, a collaboration with something that came before me. We didn’t tear the place down and start again. We engaged in intervention more than in creation. Intervention is a form of conversation. As in the concept of Dear Inga, the other half of the dialog isn’t present in the sense of a living collaborator, and yet it still brings much to the table — and to the walls, and to the ceiling, and to the space.

In my approach to design, what has come before has always played a large role. I enjoy thinking about buildings as having a life quite distinct from the plans we make for them. Buildings have their own agenda, one influenced by countless human interactions, and by the various forces of entropy that act on them. Before the printing press, monks copying print by hand would often recycle texts by rubbing the pages clean, turning them sideways, and inking new words on top. The ghost of the previous writing could be seen below as a “palimpsest.” It seems to me that there has been enough human history at this point that most of what we do and think is in service of creating future palimpsests.

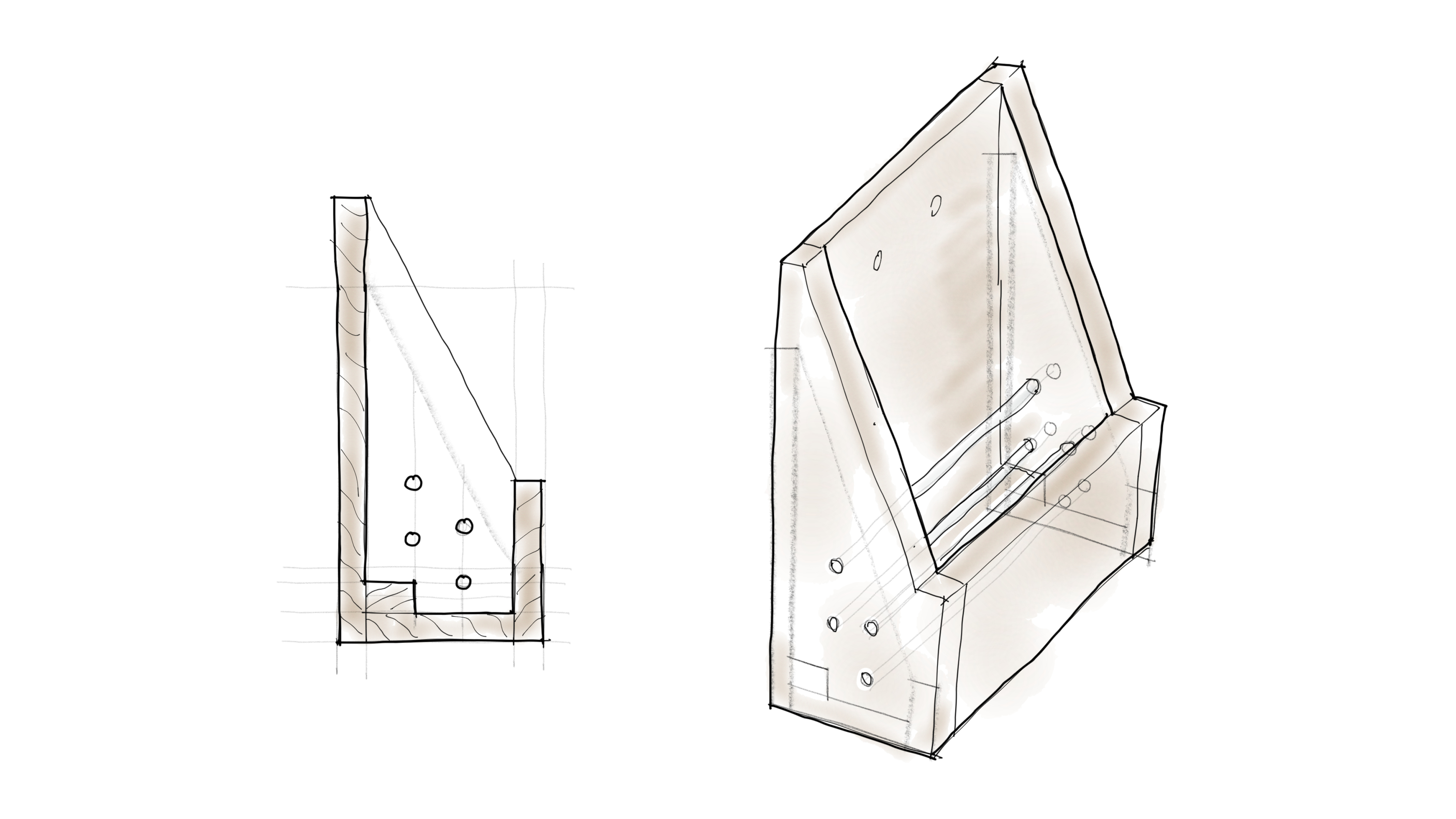

The above sketch is a rough draft of what became a menu holder. One of the beautiful things about an ongoing involvement in a project like Dear Inga is that you can continue to contribute as the place comes to life. The conversation I mentioned above doesn’t end when the place opens. In many ways, that’s just the beginning. Likewise, my work on Dear Inga didn’t end with the space. I worked on lighting fixtures with a fabricator, and, among other modest ventures, I worked on these menu holders, which I love.

When you are designing something that will be built many times you make quite a few physical versions to test it beforehand. With architecture, on the other hand, you design knowing that you don’t ever get to build it twice. This distinguishes architecture from many other design professions, and I still marvel at the leap of faith required to devote so many resources to ideas tested only on paper. To me what that ultimately means is that architecture resists being a product. It never crystalizes or stays still; it’s incompatible with mass production. It moves and evolves as it is built through countless compromises and opportunistic improvements until you open the doors and people start changing it though occupation, use, and life.

Thanks for reading.

Best,

Seth